BOZEMAN — A Montana State University satellite successfully reached orbit Wednesday after a delayed launch, and engineers are now waiting for their first communication with the spacecraft they spent seven years building.

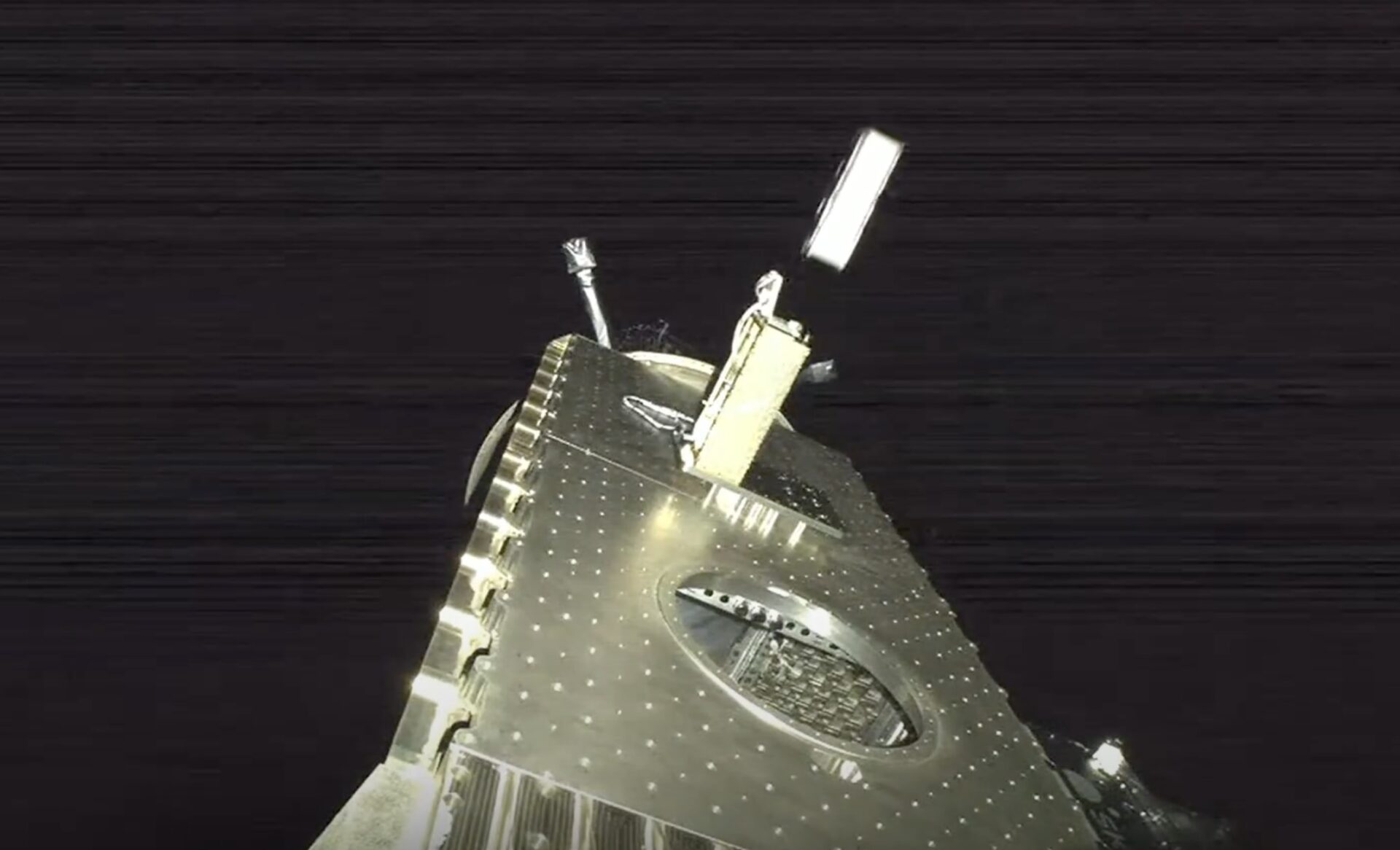

The Relativistic Electron Atmospheric Loss CubeSat, or REAL, deployed from a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket at Vandenberg Space Force Base in California at 12:16 p.m. MDT Wednesday. The launch had been scheduled for Tuesday but was postponed due to a range conflict at the local airport.

REAL was released into orbit at 1:10 p.m. MDT. As of Wednesday afternoon, the MSU team had not yet established communications with the satellite, with their first contact attempt scheduled for later that night.

“At least for those of us that watched the rocket launch in-person, it was a mix of excitement and relief,” said Tyler Holliday, senior research engineer at MSU’s Space Science and Engineering Laboratory. “We are ecstatic to see so many years of work culminate in a freshly orbiting satellite that released from the rocket as intended.”

The team expects to begin receiving science data in about two weeks as they first verify the spacecraft’s health and functionality through a slow ramp-up of operations.

Mission to study ‘killer electrons’

The NASA-funded mission represents a collaboration between Dartmouth College, Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, Boston University and MSU’s Space Science and Engineering Laboratory. The satellite will spend at least six months collecting information about dangerous solar particles that escape Earth’s magnetic field and enter the atmosphere.

“The radiation belts surrounding Earth are filled with high-energy particles traveling near the speed of light,” said Robyn Millan, the mission’s principal investigator and physics professor at Dartmouth College, during a NASA pre-launch media briefing.

Sometimes called “killer electrons,” these particles pose significant hazards to satellites and contribute to ozone destruction when they rain down on Earth’s atmosphere, Millan explained. The same particles sometimes create the Northern Lights visible in Montana.

The $1.5 million sensor designed and built by Johns Hopkins APL represents the first instrument designed to make very rapid measurements of electrons as they enter the atmosphere.

“That information will help scientists understand the forces that cause the particles to scatter,” Millan said.

Montana-built spacecraft

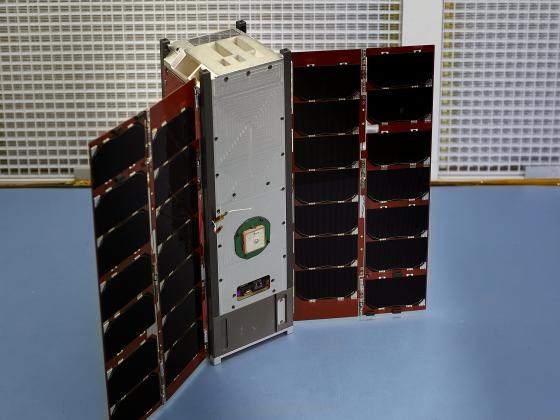

REAL comprises a deceptively simple-looking aluminum box measuring about 4 inches by 4 inches by 1 foot. The satellite houses the APL sensor, sophisticated spacecraft orientation controls, and other mission-critical electronics developed at MSU.

The satellite represents the latest achievement from MSU’s Space Science and Engineering Laboratory, founded in the Department of Physics in 2000. The lab has produced numerous small satellites over the past 25 years, helping establish standards for what are now called CubeSats.

“At that time, the small cube satellite concept had just been developed to provide affordable, real-world aerospace and satellite engineering experience to students,” Holliday said.

The total cost of the REAL project is about $5 million — a fraction of larger satellites that can cost hundreds of millions of dollars.

Student workforce

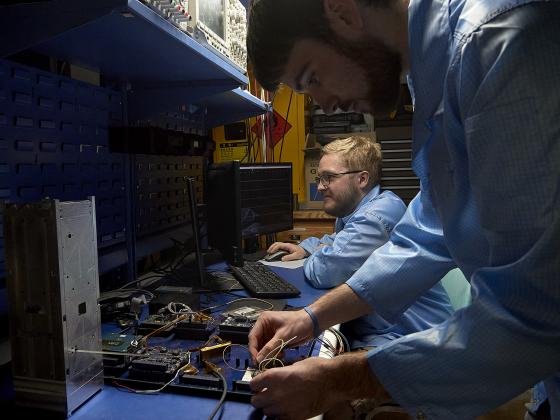

SSEL engineers have worked on REAL for seven years, with both undergraduate and graduate students contributing to the project.

“Effectively, we’re focused on educating undergraduate students and graduate students, getting them into an environment where this stuff is accessible,” Holliday said. “We give students an opportunity to come in and work on something that’s actually going into space. It’s a pretty unique thing.”

Jake Davis, now an SSEL research engineer, began working in the lab in 2020 as an undergraduate engineering student. He oversaw environmental test planning for REAL to ensure the satellite’s survival during launch and operation in space.

“It’s a big deal to make sure that you can survive your thermal environment in space and make sure you survive your vibration environment during the launch of the spacecraft,” Davis said. “It was really exciting to be able to work on that for REAL.”

Many former SSEL students have launched careers in the aerospace industry, including positions at SpaceX and Lockheed Martin.

“Our alumni, specifically from this lab, are spread out in industry,” Holliday said. “We have former students that are working at SpaceX or Lockheed Martin, and alumni that were here in the beginning years that are top executives at similar companies.”

Ground operations begin

Holliday, Davis and two other MSU team members traveled to California for the launch. Back in Montana, they and SSEL student employees will monitor REAL’s location from a ground station in Cobleigh Hall, sending commands to the satellite using software developed at MSU.

REAL is one of several scientific payloads deployed to study phenomena related to solar and geomagnetic storms.

“Being able to do something like this in Montana is incredibly valuable for all the students and for the people in the state,” Davis said.