BOZEMAN — Four months after launching into orbit, Montana State University’s REAL satellite is collecting data on dangerous space particles while engineers work to resolve technical issues that could help the mission reach its full scientific potential.

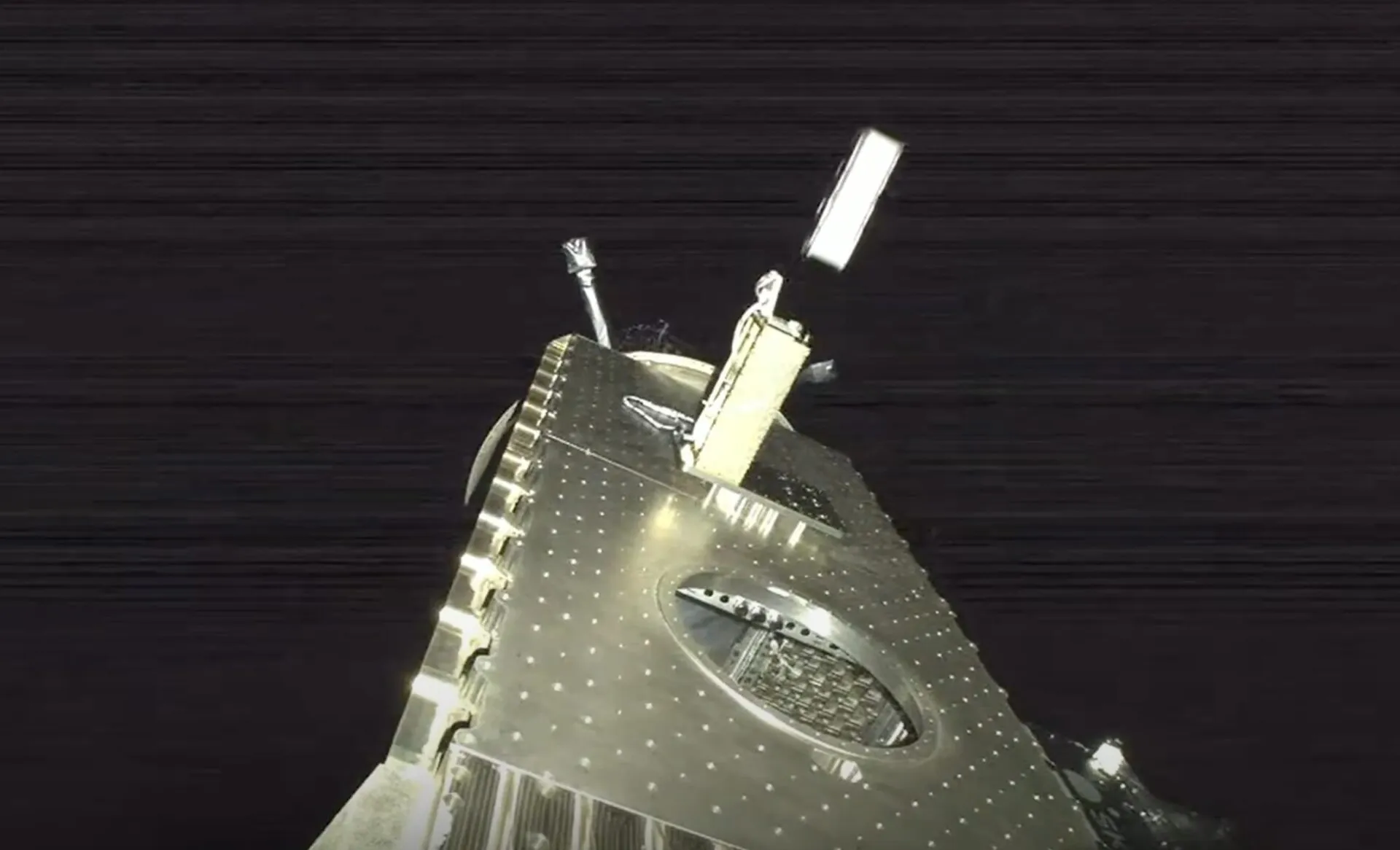

The Relativistic Electron Atmospheric Loss CubeSat, or REAL for short, deployed from a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket in July and began science operations in August. The satellite is successfully detecting traces of the high-energy “killer electrons” it was designed to study, though a memory issue within the main instrument has been processing data in an unintended way.

“Some of our early looks at the data have shown traces of what we are actually looking for,” said Tyler Holliday, senior research engineer at MSU’s Space Science and Engineering Laboratory. “However, we discovered that there was an issue within the memory of REAL’s instrument that was causing the data to be processed in an unintended way.”

The MSU team issued a series of commands to REAL last weekend intended to fix the memory problem through software updates. They expect to know within the next few weeks whether the fix was successful and the mission can meet its minimum science goals.

Communications exceed expectations

Despite the instrument challenges, REAL’s overall performance has exceeded expectations. Communications between the satellite and MSU’s ground station in Bozeman have improved significantly in recent months thanks to upgrades and repairs to ground systems.

“The relative reliability and consistency of REAL has been a surprise,” Holliday said. “While a lot of our pre-flight testing told us that this was a likelihood, we still had our reservations.”

The satellite’s main communications radio, which proved to be a failure point on MSU’s previous satellite, has performed well. Extensive pre-flight testing allowed engineers to develop failsafes that have kept the radio operating as intended.

GPS module challenges

One component that initially showed promise ultimately required the team to adapt their approach. A GPS module that struggled with signal strength during ground testing initially worked better once REAL reached orbit, successfully locking onto GPS satellites to help determine the spacecraft’s location.

However, the GPS module’s reliability degraded within a week, requiring frequent resets. The team eventually decided to turn it off and rely on alternative positioning methods they had been using during ground testing.

“That has been far more reliable,” Holliday said.

Studying ‘killer electrons’

The $5 million NASA-funded mission represents a collaboration between Dartmouth College, Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, Boston University and MSU. REAL is designed to study high-energy particles called “killer electrons” that escape Earth’s magnetic field and enter the atmosphere.

These particles, which travel near the speed of light, pose hazards to satellites and contribute to ozone destruction, according to Robyn Millan, the mission’s principal investigator and physics professor at Dartmouth College. The satellite carries a $1.5 million sensor built by Johns Hopkins APL — the first instrument designed to make very rapid measurements of electrons as they enter the atmosphere.

The mission aims to help scientists understand what forces cause these particles to scatter from Earth’s radiation belts into the atmosphere. The same particles sometimes create the Northern Lights visible in Montana.

The path from launch to operations

REAL’s journey from launch to operations has demonstrated the complexities of space engineering. Initial communication attempts in late July were hit or miss, requiring weeks of troubleshooting before the team established regular contact with the satellite in August.

The current memory issue represents another challenge in what Holliday described as a development process that was “long and fraught with difficulties.”

Holliday, who has worked on REAL for nearly five years, said the mission demonstrates the realities of space engineering, where extensive pre-flight testing can identify potential problems but cannot eliminate all unknowns.

“We still had our reservations,” he said of the satellite’s reliability, despite thorough testing. “Even during pre-flight testing we found instances where REAL’s radio could be flaky.”

The team will continue monitoring REAL’s performance in the coming weeks to determine whether the recent software fixes resolve the instrument memory issue and allow the mission to meet its science objectives.